Every iOS developer has used NSLog. We use it as a debugging tool to see the what data the system sees at a particular time while the application is running, or even to track the path our data takes when moving through our applications. But NSLog is not the be-all, end-all logging mechanism many of you think it is.

If you’re new to iOS, you may want to sit this one out until you get annoyed by NSLog - then come back here and read this.

I Use NSLog and I think it’s awesome. Isn’t that enough?

Umm… Let me count the ways. You may think of NSLog as your awesome friend with the boat who lets you join him on the weekends, but in reality he’s that guy on a Friday afternoon at the bank who’s exchanging three years worth of saved coins and asking about the interest rates on free checking accounts. I hate that guy.

There are more forces at work than you might think operating behind the scenes in order to get your log messages to both the console and into Xcode console log. Let’s go over some of the issues I have with NSLog:

Performance

NSLog is slow. This wouldn’t be so bad if it were asynchronous - but it is most definitely very synchronous. This is why you can set a breakpoint, step through your code and instantly see your NSLog statements show up in the console after you step over them. Make enough calls with NSLog in highly-iterative, performance-oriented or drawRect: code and the performance-penalty begins to add up. This is also not to say that we don’t sometimes need a synchronous logging mechanism. After all - if your code is in an unstable state, wouldn’t you want to know about both synchronously and immediately?

####Yeah? Prove it

NSLog’s poor performance is a result of a combination of a few different things. The gist of which is as follows:

- Open a new connection to ASL (Apple System Logger) daemon

- Close that connection

- Write that same message to STDERR

- Do all of the above synchronously for each call to

NSLog

As you will see in Part II of Ditching NSLog, some of the logging alternatives can be faster than NSLog by an entire order of magnitude!

Conditional Logic

NSLog is dumb. There is only one type of NSLog - the type that will display in your console. Yet, we will use our logging statements for many different purposes. Sometimes we log an error, a UI event, maybe a networking call, other times we are simply keeping track of a view controller’s view lifecycle. These are all very different types of logs that you may or may not want to show up all the time.

Wouldn’t it be nice if we could simply set a flag and only see our view lifecycle log statements? Think about that.

Beyond Development

NSLog will show up even in your production code regardless of release setting unless you deliberately do something about it. It’s not like NSAssert, which will simply get stripped out in release mode. It will rear it’s ugly head all up on your user’s devices with the same performance-penalties as before, but now nobody can even see the logs unless they can connect to their device’s console. This is serving zero purpose to aid the user’s experience in your application.

To resolve this, I’m sure we’ve all done the genius find/replace NSLog with //NSLog at least once in our careers. Yes, this technically gets rid of the NSLogs in production, but it is a huge pain to keep up with and looks ugly to boot. Then after you do this, the reverse action isn’t always as straight-forward. There may be NSLogs that you intentionally wanted commented out that are now uncommented as a result of you trying to undo your previous strike of genius. Just don’t do it. Use a conditional macro if you want some basic control over compile-time removal of NSLog in production.

There is a time and place for production logging, but chances are pretty good that you aren’t doing it right if you’re still using NSLog. Next we’ll go over the different types of logging methodologies, then discuss their role in debugging in both development and production after you ship your application to your users. That’s right - production logging!

Types of Logging

###Console Logging This is the most basic type of logging, and one which you’re probably most familiar with. The console log simply logs all of your statements to the debug log (if you’re in Xcode or in the organizer) or to Console.app if you’re running a mac app or running an app in the iPhone simulator detached from the debugger.

Practicality: *Production* (used correctly) or *development* debugging

File Logging

File logging is just like it sounds. Instead of logging to the debug console, you simply log to a file. This is best demonstrated by simply having you look in the /var/log/ folder on your Mac or Linux box. You’ll see a plethora of file logs chock full of information about what is happening on your system. For iOS, this really doesn’t make sense for your sandboxed application unless we as the developers know that we need to monitor that information.

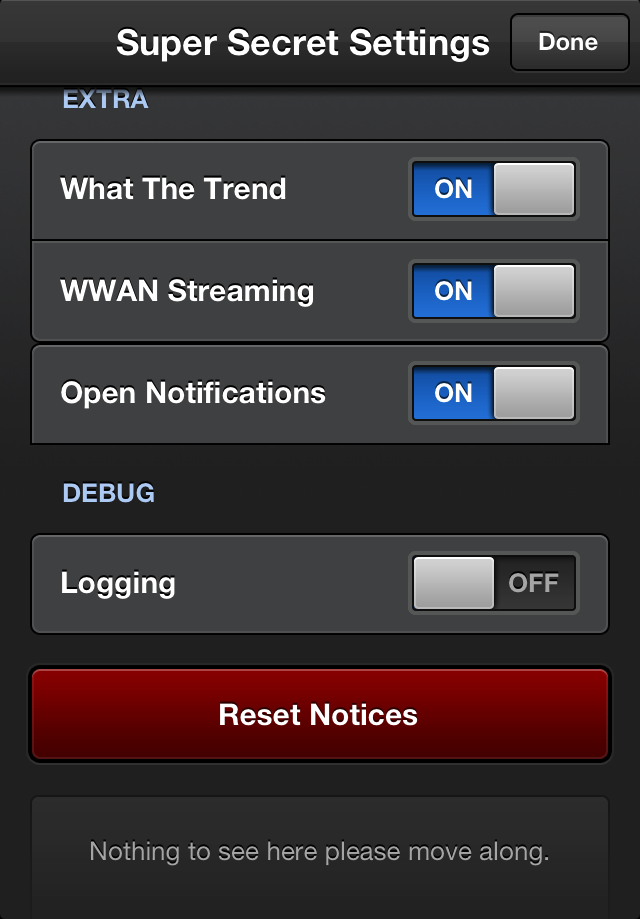

One example of this necessity is that a particular user is having an issue you’ve never even heard of before and you would like to capture the log output to see what is going on. Simply activate file logging by some super-secret menu and make an easy mechanism for the user to send you that log in an email. Just be responsible and don’t log personal information and always remember to bound the length of your logs - nobody likes 100MB log files.

Practicality: *Production* debugging

Remote Logging

This is a little more difficult to accomplish and requires either some knowhow about client/server networking on a lower level than simply API consumption, or some help from a third party library. The benefit to remote logging is that it combines all the best traits of console logging (real-time information) with file logging’s ability to not have to be physically connected to the device in order to capture the logs. This would require some participation on the user’s end, but if they’re having extreme issues, they may be more than happy to let you remotely log their device while they demonstrate the bug for you.

Practicality: *Production* debugging (with a little more user participation)

To Log, or Not to Log?

So how often should include a log statement in their code? When using the “right” logging techniques, you should log as much as possible. Some examples include:

- View/view controller life-cycles - calls to

viewDidLoad,dealloc, etc. - Errors

- Warnings

- Unexpected user input

- Whatevs

The “right” logging techniques depends highly on who you are as a programmer and even moreso on where you work. I know we have very specific coding standards at Mutual Mobile so as to increase uniformity between codebases on disparate projects. So the “right” logging techniques and practices I discuss here are those in which I believe most developers and users would benefit from. These practices are those in which you can dynamically choose which types of logs you would like to see depending on what you are working on. In not so many words: dynamic runtime logging.

Dynamic means that it involves conditional logic, and mucking with the logging mechanism at runtime means preprocessor macros are pretty much out of the picture. In Part 2, we’ll look at some techniques as well as full-blown open source libraries that will make our job of logging much easier, more dynamic, and eliminate logs in production for all but the cases we specifically care about.

Conclusion

NSLog is our dear old friend. We’ve fixed a lot of bugs using NSLog. But now it’s time to grow up. We’ve found out why NSLog really isn’t all that great, some other ways in which we can utilize logs in different formats, as well as how we can use those logs in production as well as development! Now lets build some stuff!

Check out Part II of Ditching NSLog to see how you can make your application logging work better for you!

Disclaimer: I don’t pretend to know every nook and cranny about the topics I discuss. I find teaching others is the best learning tool - and I like to learn. As a result, you may disagree or *gasp* find errors. If you disagree with any of this, write me a note at @theonlylars and let me know. I’ll either correct it or simply agree to disagree.